Mark Lilla, professor of the humanities at Columbia University, wrote an essay in the NY times entitled “The Politics of God" adapted from his book “The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics and the Modern West" in which he suggests that religious passions lie at the heart of world politics and we need to bring religion into their solution.

Mark Lilla, professor of the humanities at Columbia University, wrote an essay in the NY times entitled “The Politics of God" adapted from his book “The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics and the Modern West" in which he suggests that religious passions lie at the heart of world politics and we need to bring religion into their solution.Lilla writes: Today, we have progressed to the point where our problems again resemble those of the 16th century, as we find ourselves entangled in conflicts over competing revelations, dogmatic purity and divine duty. We in the West are disturbed and confused. Though we have our own fundamentalists, we find it incomprehensible that theological ideas still stir up messianic passions, leaving societies in ruin. We had assumed this was no longer possible, that human beings had learned to separate religious questions from political ones, that fanaticism was dead. We were wrong.

A little more than two centuries ago we began to believe that the West was on a one-way track toward modern secular democracy and that other societies, once placed on that track, would inevitably follow. Though this has not happened, we still maintain our implicit faith in a modernizing process and blame delays on extenuating circumstances like poverty or colonialism. This assumption shapes the way we see political theology, especially in its Islamic form — as an atavism requiring psychological or sociological analysis but not serious intellectual engagement. Islamists, even if they are learned professionals, appear to us primarily as frustrated, irrational representatives of frustrated, irrational societies, nothing more.

We live, so to speak, on the other shore. When we observe those on the opposite bank, we are puzzled, since we have only a distant memory of what it was like to think as they do. We all face the same questions of political existence, yet their way of answering them has become alien to us. On one shore, political institutions are conceived in terms of divine authority and spiritual redemption; on the other they are not. And that, as Robert Frost might have put it, makes all the difference. Understanding this difference is the most urgent intellectual and political task of the present time.

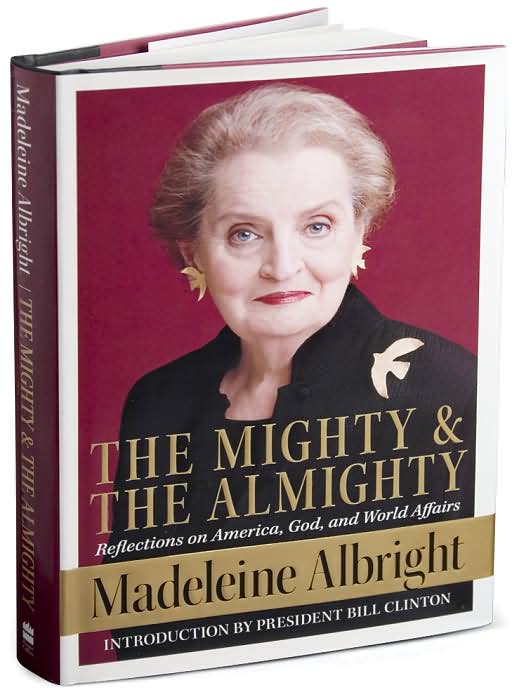

Madeline Albright makes a similar case both in her book "The Mighty and the Almighty" and also in

a recent CNN interview. Albright says that we have ignored the importance of faith in the cultures of other countries and she argues that politics and religion must be brought into our search for political solutions in many of the World’s crisis spots.

a recent CNN interview. Albright says that we have ignored the importance of faith in the cultures of other countries and she argues that politics and religion must be brought into our search for political solutions in many of the World’s crisis spots.CNN: In your book, you argue for a better understanding of religion in the U.S. foreign policy arena. Isn't that a revolutionary idea for this generation of diplomats trained more in the realist school of foreign policy?

Albright: As a practitioner of foreign policy, I certainly come from the generation of people who used to say, "X problem is complicated enough. Let's not bring God and religion into it." But through my being in office, and as I explored the subject much further in writing "The Mighty and the Almighty," I really thought that the opposite is true. In order to effectively conduct foreign policy today, you have to understand the role of God and religion. ... My sense is that we don't fully understand, because one, it's pretty complicated, and two, everyone in the U.S. believes in a separation of church and state, so you think, "Well, if we don't believe in the convergence of church and state, then perhaps we shouldn't worry about the role of religion." I think we do that now at our own peril.

Religion is instrumental in shaping ideas and policies. It's an essential part of everyday life in a whole host of countries. And obviously it plays a role in how these countries behave, so we need to know what the religious influence is.

I found the first time I went to Jerusalem, my initial reaction was, people are arguing over all this all the time, it made me think, well, there can't be a God, why would God put up with this? And then I had the total opposite reaction. One that stays with me, which is that there are so many holy places and symbols there, and all anybody talks about is their relationship to those symbols and to God, and therefore the power of God must be so strong there. I just think that it would be much better if people could figure out ... how to agree about it.

CNN: So, therefore, how to figure out the fate Jerusalem is the perfect example of why we need to include religious understanding in our foreign policy.

Albright: Definitely. I am not a theologian, and I have not turned into a religious mystic, but I am a practical problem solver. So I'm looking at religion from the perspective of how knowledge about what people believe in can be useful in terms of trying to resolve the most serious disputes. I think one of the major problems is that here in the United States, particularly, there is very little understanding of Islam. We all act as if Islam is a monolithic religion and that all Muslims live in the Middle East. The bottom line is most Muslims in the world don't live in the Middle East. They live in Indonesia, or Malaysia, or India, um, Pakistan. Second, there are a number of different sects within Islam. Now I think more people understand the difference between Shia and Sunni, but that is just the beginning. We really do not know anything about it.

Does the U.S.A need more 'religion' in its foreign policy ?

Posted August 21, 2007

5 comments:

I have been watching the CNN series God’s Warriors which I recommend strongly. The first one on the Jewish warriors gives me no hope of any solution to the Palestinian issue. I read the interview CNN did with Albright and she is absolutely right when she says:

Anybody that can really solve that issue is a Solomon. With this being holy to all three of the Abrahamic religions, it's very difficult. And religion, rather than bringing people together on this, is driving them apart, which ... I don't think [is] what is intended. It's so interesting; we're talking about the whole issue of sovereignty here. Because the parties both believed that God gave them that little piece of land, we started playing with a term, which was that it belonged to God. Divine sovereignty. Anybody who's been to Jerusalem can see why it is so complicated. Physically, religious holy places are completely intertwined, one on top of the other. So in many ways, there's great appeal to saying it belongs to God, and then trying to figure out how it [is] administered, maybe through some international group of some kind.

I seem to remember, Michael, that you suggested a similar solution to the Jerusalem problem to turn it into a separate state similar to Vatican City which is a separate state in the heart of Italy ‘ruled’ by the Roman Catholic church. Why can Jerusalem not become the state of “Jerusalem City’ and be governed by the Pope, the Archibishop of Canterbury, and their equivalents in the Jewish and Muslim religions?

The problem of this city is more religious than political and each state could still regard Jerusalem as its ‘capital’. Why can it not be the capital of both Israel and a Palestinian State?

Sincerely,

Vinny

Hello everyone

This is my first post. I really like this blog and the topics that it deals with. I have been reading it with interest for some time and felt it was time to plunge in.

It seems obvious from the series “God’s Warriors” that some radical new thinking or change in people’s world views will be needed before anything changes in the areas where the fundamentalists collide. It seems to have taken about 400 years in Ireland for the problems there to reach any level of sanity and IMHO that only occurred because of the rise of the internet, ease of travel, and the economic boom in Ireland. All of these had nothing to do with religion. People there developed a wider world view and instead of sitting around unemployed in state of hopelessness they saw economic blessings could be had.

So we probably will have to be patient with the Middle East – the Jewish/Arab Muslim conflict – the Sunni/Shiite conflict – the Theist/Secular Humanist conflict – etc etc and wait until political, economic, and religious evolutions occur in a direction that these problems will go away. I fear that most of them will still be here at the end of my lifetime but I could be wrong and of course I pray (metaphorically) that I am.

The stuff from Albright and Lilla is right on. I haven’t read either of their books but they have been added to my summer reading list!

Best wishes,

Jill Johansson

Christopher Hitchens (author of “The God Delusion”) has a review in Slate magazine (posted online on August 27) entitled God’s Still Dead in which he says that Mark Lilla doesn't give us enough credit for shaking off the divine. Hitchens presents a good review both of Lilla’s article in the NYT and also on Lilla’s book “The Stillborn God”

Hitchens writes as follows:

Begin quote

Those of us in the fast-growing atheist community who have long suspected that there is a change in the zeitgeist concerning "faith" can take some encouragement from the decision of the New York Times Magazine to feature professor Mark Lilla on the cover of the Aug. 19 edition. But we also, on reading the extremely lucid extract from his new book, The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics, and the Modern West, are expected to take some harsh punishment. Briefly stated, the Lilla thesis is as follows:

• The notion of a "separation" of church and state comes from a unique historical contingency of desperate and destructive warfare between discrepant Christian sects, which led Thomas Hobbes to propose a historical compromise in the pages of his 17th-century masterpiece, Leviathan. There is no general reason why Hobbes' proposal will work at all times or in all places.

• Human beings are pattern-seeking animals who will prefer even a bad theory or a conspiracy theory to no theory at all, and they are thus (in an excellent term derived by Lilla from Jean-Jacques Rousseau) by nature "theotropic," or inclined toward religion.

• That instinct being stronger than any discrete historical moment, it is idle to imagine that mere scientific or material progress will abolish the worshipping impulse.

• Liberalism is especially implicated in this problem, because the desire for a better world very often takes a religious form, and thus it is wishful to identify "belief" with the old forces of reaction, because it will also underpin utopian or messianic or other social-engineering fantasies.

Taken separately, all these points are valid in and of themselves. Examined more closely, they do not cohere as well as all that. In the first place, it is not correct to say that modernism relied on a conviction about the steady disappearance of religious belief. Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, to take two very salient examples, looked upon religion as virtually ineradicable—the former precisely because he did identify it with secular yearnings that would be hard to satisfy, and the latter because he thought it originated in our oldest mistake, which was (and is) wishful thinking.

In the second place, it is interesting to find Lilla conceding—though not in so many words—that religion is closely related to the totalitarian. As he phrases it when writing about Orthodox Jewish and Islamic law (and as was no less the case for Christianity in its pre-Hobbesian heyday), divine or revealed teaching is "meant to cover the whole of life, not some arbitrarily demarcated private sphere, and its legal system has few theological resources for establishing the independence of politics from detailed divine commands." How true. Now, there is one thing one can say with relative certainty about the totalitarian principle, which is that it has been repeatedly tried and has repeatedly failed. Try and run a society out of the teachings of one holy book, and you will end with every kind of ignominy and collapse. There is no reason at all to confine this grim lesson to the Christians who were butchering each other between the Thirty Years' War and the English Civil War; even the Jews who established the state of Israel and the Muslims who set up Pakistan understood the importance of some considerable secular latitude (as did the Hindus who were the majority in independent India). In other words, while it may be innate in people to be "theotropic," it is also quite easy for them to understand that religion is a very potent and dangerous toxin. Never mind for now what Islamist fundamentalism might want to do to us; take a look at what it did to the Muslims of Afghanistan.

So, when Lilla says that the American experiment (in confessional pluralism and constitutional secularism) is "utterly exceptional," he forgets that there had to be many dress rehearsals for this and that only a uniquely favorable opportunity was the really "exceptional" condition. Men like Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine had been eagerly studying the secular and agnostic and atheist thinkers of the past and present, from Democritus to Hume, and hoping only for a chance to put their principles into action. There are many minds in today's Muslim world who have, by equally scrupulous and hazardous inquiry, come to the same conclusion. It is repression as much as circumambient culture that prevents the expression of the idea (as it did for many, many, Christian and Western centuries).

Lilla's most brilliant point concerns the awful pitfalls of what he does not call "liberation theology." Leaving this stupid and oxymoronic term to one side, and calling it by its true name of "liberal theology" instead, he reminds us that the eager reformist Jews and Protestants of 19th-century Germany mutated into the cheerleaders of Kaiser Wilhelm's Reich, which they identified—as had Max Weber—with history incarnate. Lilla might have added, for an ecumenical touch, that Kaiser Wilhelm, in launching the calamitous World War I, was also the ally and patron of the great jihad proclaimed by his Ottoman Turkish subordinates. So, could we hear a little less from the apologists of religion about how "secular" regimes can be just as bad as theocratic ones? Of course they can—if they indulge in acts of faith and see themselves as possessing supernatural authority.

Lilla goes on to cite the many liberal religious figures who became apologists for Nazism and Stalinism, and I think he is again correct to stress the Jewish and Protestant element here, if only because most of the odium has rightly fallen until now on the repulsive role played by the Vatican. So, what is he really saying? That religion is no more than a projection of man's wish to be a slave and a fool and of his related fear of too much knowledge or too much freedom. Well, we didn't even need Hobbes (who wanted to replace a divine with a man-made dictator) to tell us that. To regret that we cannot be done with superstition is no more than to regret that we have a common ancestry with apes and plants and fish. But millimetrical progress has been made even so, and it is measurable precisely to the degree that we cease to believe ourselves the objects of a divine (and here's the totalitarian element again) "plan." Shaking off the fantastic illusion that we are the objective of the Big Bang or the process of evolution is something that any educated human can now do. This was not quite the case in previous centuries or even decades, and I do not think that Lilla has credited us with such slight advances as we have been able to make.

End quote

Ever

DM

DM, back in May 2005 Lilla had another article in the NYTimes under the title Essay: Church and State some comments of which are very appropriate given the ‘revelations’ about God’s Warriors in the three CNN programs.

What he said about the trends in the religious views of U.S. Christians fits right in with what CNN presents in their third program on the “Christian Warriors”.

It appears that there are limits to the liberalization of biblical religion. The more the Bible is treated as a historical document, the more its message is interpreted in universalist terms, the more the churches sanctify the political and cultural order, the less hold liberal religion will eventually have on the hearts and minds of believers. This dynamic is particularly pronounced in Protestantism, which heightens the theological tension brought on by being in the world but not of it. Liberal religion imagines a pacified order in which good citizenship, good morals and rational belief coexist harmoniously. It is therefore unprepared when the messianic and eschatological forces of biblical faith begin to stir.

The leading thinkers of the British and American Enlightenments hoped that life in a modern democratic order would shift the focus of Christianity from a faith-based reality to a reality-based faith. American religion is moving in the opposite direction today, back toward the ecstatic, literalist and credulous spirit of the Great Awakenings. Its most disturbing manifestations are not political, at least not yet. They are cultural. The fascination with the ''end times,'' the belief in personal (and self-serving) miracles, the ignorance of basic science and history, the demonization of popular culture, the censoring of textbooks, the separatist instincts of the home-schooling movement -- all these developments are far more worrying in the long term than the loss of a few Congressional seats.

No one can know how long this dumbing-down of American religion will persist. But so long as it does, citizens should probably be more vigilant about policing the public square, not less so. If there is anything David Hume and John Adams understood, it is that you cannot sustain liberal democracy without cultivating liberal habits of mind among religious believers. That remains true today, both in Baghdad and in Baton Rouge.

Reason rules!

Liz

After watching the three programs I find that my initial negative reaction to Muslim women’s insistence on wearing the veil has moderated greatly. I understand, and indeed empathize, with the view that women tend to be more degraded in Christian societies than in the Muslim counterparts.

Frankly I am starting to think that exposure of women’s breasts, their midriffs, bellies, backs, and bums has gone to the point that it has become offensive to many women like myself. The Christian societies seem to regard women purely as sexual beings serving some sort of an entertainment role for society.

Which women are held up to our youth as examples by the media? Paris Hilton? Lindsay Lohan? Is that what our daughters have to inspire them?

Many of the young Muslim and Christian women portrayed in God’s Warriors were admirable in my view and I support their decision to protect their God-given dignities.

Joan

Post a Comment