In the December 30, 2007 issue of the NY Times Anthony Tommasini has some interesting comments on whether a patience to listen to classical music is alive and well.

In the December 30, 2007 issue of the NY Times Anthony Tommasini has some interesting comments on whether a patience to listen to classical music is alive and well.He writes in part: Reports about the diminishing relevance of classical music to new generations of Americans addled by pop culture keep coming. Yet in my experience classical music seems in the midst of an unmistakable rebound. Most of the concerts and operas I attended this year drew large, eager and appreciative audiences. Classical music invites listeners to focus, to take in, to follow what is almost a narrative that unfolds over a relatively long period of time.

Length itself is one of the genre’s defining elements. I do not contend that classical music is weightier than other types of music. Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony is no more profound than “Eleanor Rigby.” But it’s a whole lot longer. Even a 10-minute Chopin ballade for piano, let alone Messiaen’s 75-minute “Turangalila Symphony,” tries to grapple with, activate and organize a relatively substantial span of time. Once you accept this element of classical music, the reasons for other aspects of the art form — the complexity of its musical language, the protocols of concertgoing — become self-evident.

Structure in classical music is the easiest element to describe yet the hardest to perceive. Too often writers of program notes take the easy way and simply lay out the road map of a piece: first this happens, then that happens, then the first thing returns in a modified form and so on. But perceiving these structures as a listener is another matter. When I was around 13 and enthralled by Mozart’s “Jupiter” Symphony and Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, I didn’t have the vaguest notion of how sonata form worked or what a rondo was. That I grew so familiar with these big pieces, though, does not mean I grasped how they were organized. Still, I intuitively sensed that they were monumental in some way, for the great classical works seemed to have an inexplicable and inexorable sweep. Years later, I tried to help students hear what seemed to me astounding similarities between, say, a song-and-dance from Monteverdi’s “Orfeo” and “America” from Bernstein’s “West Side Story.” I broke down symphony movements by Beethoven and Shostakovich into constituent parts. Quite a few students were openly resistant, others mildly curious; some were surprisingly engaged.

Once in a while someone would come back from a concert having had an epiphany. More often than not, though, these epiphanies did not turn the students into devotees of classical music. Why not? My guess is that the pieces played were simply too long. Taking in a concert involves a major time commitment. You sit in silence for extended periods and pay attention to live performances that, however viscerally involving and sonically impressive, are visually unremarkable. Operas, of course, tend to be even longer. But opera is a total-immersion experience, with characters and costumes, like going to the theater.

In an essay in The New York Times in June, Professor Kramer called for classical music presenters to follow the lead of enterprising art museums, which have had much success in presenting new and old art in interactive, stimulating and demystifying ways. A concert can offer pre-performance talks, interactive video displays in the lobby and spoken comments by the performers onstage. But at some point the talking stops, the performance begins, and the audience is asked to be quiet and pay attention.

Even so, the act of communal listening need not be reverential. And classical music has its “wow” factors too. What could be more entertaining than a dynamic performance of Prokofiev’s shamelessly theatrical Third Piano Concerto, with its monstrously difficult piano part? And if your mind wanders during “La Mer,” by Debussy, and you start focusing on the kinetic playing style of an attractive young violinist in the orchestra, then, as Professor Kramer suggests, just go with it. Creating an atmosphere conducive to listening does not mean that concert halls have to be stuffy. Dress codes of any kind should disappear. Go ahead and replace some rows of seats at Avery Fisher Hall with rugs and pillows to recline on, if it helps. Much less drastic innovations have proved effective. Lincoln Center’s series A Little Night Music presents 60-minute programs beginning at 10:30 p.m. Only about 160 people can be accommodated. Patrons share small round cocktail tables and have free glasses of wine.

But to claim a listener’s attention, a substantial classical piece must entice the dimension of human perception that responds to large structures and long metaphorical narratives. This, more than anything lofty about the music, accounts for the greater complexity, typically, of classical works in comparison with more popular styles of music. One reason “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” stunned my generation at its 1967 release was that this Beatles album was not just a collection of songs but a whole composition. I remember sitting in my freshman dorm room with friends, listening to the entire album in silence. That was a new experience in rock. “Sgt. Pepper” pointed the way to longer total-concept albums like Radiohead's “In Rainbows,” the big news in pop music today.

No one was better than Leonard Bernstein at drawing new listeners to classical music. When he presented his Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic, he didn’t have music videos or PowerPoint, and didn’t need them. It was just our amazing Uncle Lenny explaining the content of a piece, conveying its character and revealing its secrets. But when the explanations were over, Bernstein would turn to his young listeners and say, “Are you ready?” The time had come to settle down and focus as the orchestra performed the piece in question. Instilling audiences of all ages with the ability — and patience — to listen to something long was crucial to an appreciation of classical music. It still is.

Cocktail bars for classical music?

Posted December 31, 2007

An article in Wikipedia discusses how: "the word

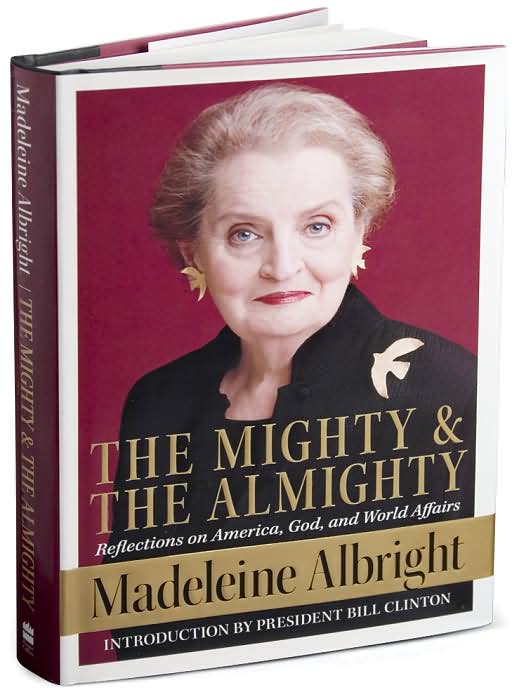

An article in Wikipedia discusses how: "the word  The Publisher of Christopher Hitchens' latest book writes:

The Publisher of Christopher Hitchens' latest book writes: In the November 18, 2007 issue of the

In the November 18, 2007 issue of the  Karen Armstrong is the author of nearly twenty books, including

Karen Armstrong is the author of nearly twenty books, including

rch in the Dorset village of Stinsford, a boy named Thomas Hardy had an experience that, more than sixty years later, he remembered as causing him “much mental distress.” As the boy watched the priest deliver the sermon, Hardy recalled in his autobiography, “some mischievous movement of his mind set him imagining that the vicar was preaching mockingly, and he began trying to trace a humorous twitch in the corners of Mr. S—’s mouth, as if he could hardly keep a serious countenance. Once having imagined this the impish boy found to his consternation that he could not dismiss the idea.”

rch in the Dorset village of Stinsford, a boy named Thomas Hardy had an experience that, more than sixty years later, he remembered as causing him “much mental distress.” As the boy watched the priest deliver the sermon, Hardy recalled in his autobiography, “some mischievous movement of his mind set him imagining that the vicar was preaching mockingly, and he began trying to trace a humorous twitch in the corners of Mr. S—’s mouth, as if he could hardly keep a serious countenance. Once having imagined this the impish boy found to his consternation that he could not dismiss the idea.”

to be the last man standing with Wade—the man who successfully delivers the criminal to the law in Yuma.

to be the last man standing with Wade—the man who successfully delivers the criminal to the law in Yuma. Wade's odd brand of

Wade's odd brand of

Mark Lilla, professor of the humanities at Columbia University, wrote an essay in the NY times entitled

Mark Lilla, professor of the humanities at Columbia University, wrote an essay in the NY times entitled  a recent

a recent